美国正滑向“盗贼统治”吗

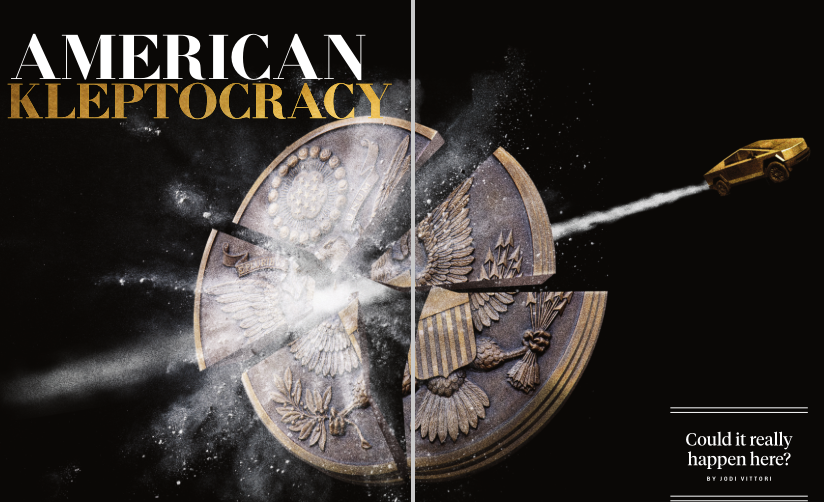

本文编译自美国知名国际关系期刊《外交政策》2025年春季刊,作者为乔治城大学外交学院教授乔迪·维托里(Jodi Vittori)。文章以批判性的视角,深入探讨了特朗普在其第二个总统任期内,一系列举措可能对美国民主制度构成的潜在威胁。作者的核心论点是,这些举措正在系统性地瓦解美国长期建立的反腐败规范与机构,使国家显现出滑向“盗贼统治”(Kleptocracy)的危险迹象。

当巨变来临时,人们总会寻找一本“用户手册”来指引方向。我们将迎来新的生活模式与未来预期,而美国正在迅速演变的腐败图景也不例外。自去年十一月唐纳德·特朗普当选总统,及其就职以来加速的制度与人事变革,已将美国人推入了一个全新的政治领域。

其中,反腐机构与规范的瓦解尤为引人注目。司法部长帕姆·邦迪(Pam Bondi)已下令司法部(Justice Department)优先处理与犯罪集团相关的案件,并关闭了“盗贼抓捕特遣队”(Task Force KleptoCapture)和“盗国者资产追回计划”(Kleptocracy Asset Recovery Initiative)。特朗普本人也下令,在六个月内暂停对《反海外腐败法》(Foreign Corrupt Practices Act)的新调查或执法行动 。

译者注:《反海外腐败法》(FCPA)

这是美国于1977年制定的法律,旨在禁止美国公司和个人向外国政府官员行贿以获取商业利益。暂停执行该法案被作者视为削弱美国海外反腐承诺的信号。

尽管这些举措主要针对美国企业在海外的腐败行为,但国内的反腐规范同样面临着迅速而巨大的压力。特朗普政府已解雇了至少17名监察长(inspectors general)——这些职位是在“水门事件”后设立的,旨在独立监督政府机构内的管理不善和权力滥用 。此外,总统还发布了一项行政命令,削弱了联邦贸易委员会(Federal Trade Commission, FTC)和证券交易委员会(Securities and Exchange Commission, SEC)等机构的独立性,而这些机构在发现和惩罚腐败方面扮演着重要角色 。

对一些人来说,这些变化已超越了新政府上台后常见的政策调整。它似乎催生了一套新的政治词汇。例如,“劣等统治”(kakistocracy,指由最不称职或最无能的公民治理的社会)一词,在成为《经济学人》杂志2024年的年度词汇之前,鲜有人知 。权威评论家们将那些在特朗普就职典礼上占据最佳位置的科技高管,称为美国的新“寡头”(oligarchs)。前总统乔·拜登(Joe Biden)也在其告别演说中警告:“一个寡头政治正在美国形成。” 而参议员伯尼·桑德斯(Bernie Sanders)的用词则更为严厉,他称特朗普政府正“非常迅速地将这个国家推向盗贼统治(kleptocracy)” 。

这些术语在定义和实践中究竟意味着什么?其中哪些(如果有的话)可以准确地用来描述美国正在迎来的政治秩序?

一、何为腐败,何为盗贼统治?

首先需要界定的,是腐败本身。特朗普曾在与顾问埃隆·马斯克(Elon Musk)共同露面时说:“我竞选时就说过政府是腐败的——而且非常腐败。” 事实上,根除所谓“深层政府”(deep state)官僚体系中的贪污,正是马斯克为其主导的“政府效率部”(Department of Government Efficiency, DOGE)设定的目标之一 。

译者注:深层政府(Deep State)

这是一个在美国右翼话语中常见的阴谋论概念,指称那些通过非民主选举产生的、长期盘踞在政府机构、情报部门和军队中的官僚与精英,在幕后实际操控国家,并阻挠民选总统(尤其是特朗普)的议程。

尽管关于腐败没有全球统一的定义,但最普遍的定义之一,如倡导组织“透明国际”(Transparency International)所言,是“为一己私利而滥用受托权力” 。

腐败有多种类型,而当前最令人担忧的是“巨型腐败”(grand corruption)。巨型腐败是指公共机构被统治精英网络所把持,用以窃取公共资源以谋取私利 。它涉及贿赂、勒索、裙带关系、任人唯亲、司法欺诈、选举舞弊、挪用公款、权钱交易和利益冲突等多种行为 。人们担忧,特朗普政府通过瓦解反腐体系,可能正在为未来的巨型腐败敞开大门 。

与巨型腐败相对的是“轻微腐败”(petty kind),即公民在医院、学校和警察局等地被索要贿赂或其它好处时所遇到的情况 。

而“盗贼统治”(Kleptocracy)则将腐败——即便是巨型腐败——提升到了一个全新的层面。除了“盗贼的统治”(rule by thieves)这一字面意思外,它没有唯一的特定定义 。盗贼统治具有几个突出特征:其一,腐败是系统性的、深度网络化的和自我强化的 ;其二,其后果会扭曲长期的政治和社会经济格局,对普通民众生活造成巨大冲击 ;其三,在这种体制下,巨型腐败丑闻并非异常现象,而是国家的核心功能和统一目标 。

在盗贼统治中,被称为“寡头”(oligarchs)的关键精英人物至关重要 。这个词源于古希腊语,亚里士多德将其描述为“由有产者掌握政府” 。根据此定义,一个国家要成为寡头政治,富人必须能够影响政府,以牺牲广大民众的利益为代价来保护自己的财富和权力 。

二、影响市场:盗贼统治的经济后果

学者迈克尔·约翰斯顿(Michael Johnston)在尝试对不同国家的盗贼统治运作方式进行分类时,将美国归入他所称的“影响市场”(Influence Markets)之列——即全球民主善治的领导者 。历史上,没有任何一个被视为“影响市场”的国家演变成一个完全的盗贼统治 。然而,当一个同时也是“影响市场”的大国成为盗贼统治时,会发生什么,我们并没有历史模型可循 。

倘若美国陷入盗贼统治,少数赢家将获益巨大。在盗贼统治下,寡头们享有优先的政策准入和公然的巨型腐败,这意味着政府采购价格上涨,公共服务进一步私有化,各种苛杂费用层出不穷 。更多的公路变成收费公路,从航空公司到酒店再到信用卡的各类企业都可以随意增加费用和附加费 。随着寡头们进一步避税,税收负担将更沉重地落在穷人和中产阶级身上 。

社会福利项目——特别是为国家最贫困公民设立的项目——在盗贼统治中会日益被削减、资金不足或完全取消 。最近通过的众议院预算提议延长特朗普2017年的减税政策(主要惠及富人),同时计划在10年内削减2万亿美元的支出 。本身就极为富有的商务部长霍华德·卢特尼克(Howard Lutnick)近期称社会保障、医疗补助和医疗保险是“错误的”,这是一个更令人担忧的信号 。

三、分裂与征服:盗贼统治的政治策略

政治化的机构,尤其是执法机构,是维持盗贼统治运行的必要条件 。正如秘鲁前独裁者奥斯卡·贝纳维德斯(Óscar Benavides)所说:“给我的朋友一切;对我的敌人,依法办事。” 委内瑞拉和俄罗斯的公司都清楚,与政府作对会招来税务警察、毁灭性的税单和破产的命运 。

展望未来,如果某些行政命令和政策得以实施,可能会进一步将美国推向盗贼统治。其中最关键的是“F项附表”(Schedule F),该计划允许将公务员归入一个工作保障较少的雇佣类别,从而削弱了150年来的公务员制度改革成果 。实施该计划将使美国回到19世纪普遍存在的“政治分肥制”(spoils system)。

译者注:“F项附表”(Schedule F)与“政治分肥制”(Spoils System)

“政治分肥制”指赢得选举的政党,将政府职位作为战利品酬谢给其支持者和党羽的做法。为根除其弊病,美国在19世纪末开始进行公务员制度改革,建立了基于功绩和专业能力的职业文官体系。“F项附表”是特朗普在第一个任期内提出的行政令,旨在将数万名被认为具有“政策制定”角色的联邦雇员重新归类,使其更容易被解雇和替换,这被批评者视为恢复“政治分肥”、安插政治忠诚者的举动。

这些行政命令、可疑的人事任免、被束缚的司法部、受削弱的独立机构,以及被剥夺资金和权力的公务员体系,其结果是,那些想要为一己私利改造美国联邦机构的人,正处于有能力这样做的权力位置上 。此外,所有这些举措的快速启动,使得各州、法院、公民社会和记者们更难做出有效回应;这正是特朗普前顾问史蒂夫·班农(Steve Bannon)著名的“用垃圾淹没舆论场”(flood the zone with shit)策略的实际应用 。

一个团结起来反对寡头的反对派,是盗贼统治最大的威胁,因此他们必须维持“分裂与征服”(divide-and-conquer)的策略 。特朗普在其任期初期的许多决策似乎都旨在重新激化两极分化 。例如,他大规模赦免因2021年1月6日冲击国会山事件而被起诉的1500多人,这似乎并非为了团结国家 。持续进行的军方领导层清洗,也进一步加剧了分裂 。

四、我们能做什么?

这些行动加总起来是否构成一个完全的盗贼统治,还有待观察。但可以肯定的是,盗贼统治是一种深思熟虑的策略,而非偶然的机会 。没有“意外的盗贼统治” 。

反盗贼统治(dekleptification)研究表明,清除社会盗贼统治的最佳时机,就是当该社会的规则和制度处于变动之中时——在美国,就是现在 。

世界各地的人们都曾与盗贼统治网络作斗争,并常常取得成功。这意味着,有大量的反盗贼统治经验教训可供忧心忡忡的美国人借鉴,作为他们制定自身策略和战术的一部分 。数十年来,美国人一直试图告诉其他国家的公民如何修正他们的政府,现在也许是时候角色互换了 。至于巨型腐败,美国人自己也有反抗的历史,包括在“镀金时代”(Gilded Age)。他们可以寻找并选举像西奥多·罗斯福(Theodore Roosevelt)那样坚定的反腐改革者,重振艾达·B·威尔斯(Ida B. Wells)和艾达·塔贝尔(Ida Tarbell)那样的“扒粪运动”(muckraking),并重新投入到静坐、抗议游行、抵制和其他抵抗行动中去 。毕竟,这些贯穿了美国历史,是民权运动的标志 。【全文完】

文章分析

这篇发表于《外交政策》(Foreign Policy)杂志的文章我认真看过了,选题很有深度,也很有挑战性。它预测了特朗普再次执政后,美国政治可能出现的深刻变化。作为你的新闻编译实践的第一步,我先来帮你分析一下这篇原文。

这篇文章的核心主题是:

通过剖析特朗普政府在第二个任期内一系列削弱现有制度的举措,论证美国正显现出滑向“盗贼统治”(Kleptocracy)的危险迹象。对于我们“川透社”的读者来说,这篇文章提供了理解当前美国深度政治焦虑的一个独特窗口,但其中涉及的大量美国政治背景知识,确实是编译工作的重点和难点。

首先,让我们深入文章的政治文化背景。文章提及的“盗贼统治” (kleptocracy)、“劣等统治”(kakistocracy) 和“寡头政治”(oligarchy)等概念,对国内读者可能比较陌生。它们描绘的是一种由最不胜任的、最贪婪的精英阶层通过窃取公共资源来统治国家的极端政治形态。文章将特朗普政府解散反腐机构(如“KleptoCapture”项目)、开除十多位拥有独立监督权的监察长(inspectors general)、以及发布行政令(如“F项附表”)削弱公务员独立性等行为,都视为是系统性地侵蚀民主“防腐墙”的证据。你需要向读者解释,监察长制度是“水门事件”后设立的独立监督机构,而“F项附表”则旨在瓦解已实行一个半世纪的、旨在防止政治分肥的公务员择优录取制度。不理解这些制度的历史和功能,就很难理解作者为何会对这些变化感到警惕。

在体裁与结构方面,这篇文章并非追求时效性的“硬新闻”,而是一篇逻辑严谨、分析深入的政论性特稿或深度分析报道。它没有采用将核心事实置于开头的“倒金字塔体” ,而是更接近我在教程中提到的“华尔街日报体”的逻辑论证结构 。文章以近期发生的令人不安的政治变革作为“钩子” ,随即进入对核心概念(腐败、盗贼统治等)的定义与阐释部分,然后层层递进地提供证据来支撑其核心论点,最后以探讨反抗策略作结。这种结构旨在引导读者进行深度思考,而非仅仅传递信息。

关于信源与立场,这篇文章来源《外交政策》杂志,其作者是乔治城大学的教授 ,这赋予了文章很强的学术性和权威性。然而,我们必须认识到,它带有鲜明的批判特朗普政府的政治立场。文章使用的语言(如“瓦解”、“破坏”、“令人担忧的”)带有强烈的情感和价值判断色彩。可以说,这是一篇典型的美国自由派或中左翼知识分子对当前政治走向的深度忧思 。在编译时,忠实地再现这种批判性立场,而不是试图将其“中立化”,是理解和翻译原文的关键。

最后,从跨文化传播的角度看,这篇文章极具特色。它将一个纯粹的美国内政问题,通过与匈牙利、俄罗斯、南非等国的类比,置于一个全球性的“民主衰退”框架下进行讨论。更有趣的是,它颠覆了传统上由美国向外输出“善治”经验的模式,反过来建议美国人或许应该向其他国家的人民学习如何反抗“盗贼统治”。这本身就是一个非常值得在编译中向读者点明的、极具讽刺意味的跨文化传播现象。

编译策略

用“单篇编译”的方式来处理这篇文章,这个想法非常好。之所以说这个选择好,是因为原文虽然逻辑严谨、论证有力,但它面向的是对美国政治有深度了解的读者。如果采用“全译”,大量的背景知识空白会使我们的读者感到困惑,大大削弱文章的传播效果;如果采用“节译”,又很容易损失原文层层递进的论证力量,使其深度打折。而“单篇编译”则允许我们在尊重原文核心论点和结构的基础上,进行必要的“再创作”,这恰恰是处理此类深度政论文章的最佳方式。

首先,重拟标题和导语,增加背景阐释。原文的标题《伟变将至...》(When great changes are afoot...)文学性有余,但新闻性不足。我们可以提炼其核心论点,拟定一个更直接、更能吸引读者眼球的中文标题,例如点明“盗贼统治”风险的标题。导语部分,我建议你需要将原文的核心观点——即特朗普政府系统性地侵蚀制度、可能导致美国走向“盗贼统治”——进行提炼,改写成一个更为简洁有力的摘要式导语,开宗明义地告诉读者这篇文章要谈论的核心问题是什么。对于我们之前分析过的那些背景知识,比如“F项附表”、“监察长制度”等,你可以通过在正文中以括号加注原文、或在关键段落后附上“背景链接”、“延伸阅读”等方式,用简洁的语言进行补充说明。这样既能保证正文的流畅性,又能帮助读者扫清阅读障碍。

其次,保留逻辑,优化结构。原文“提出问题-界定概念-分析论证-总结展望”的逻辑链条非常清晰,我们在编译时应予以保留。但是,原文段落普遍较长,为了适应中文读者的阅读习惯,你可以适当地将一些长段落拆分为几个短段落,并添加小标题来串联全文,使文章的脉络更加清晰可辨。

最后,我建议在文章开头加上一段**“编者按”**。在这段按语中,我们可以简要介绍原文的出处《外交政策》杂志及其基本立场,并提示读者本文代表了美国特定知识群体对当前政治的一种深度忧虑和批判性视角。这不仅体现了我们“川透-社”的专业性,也能更好地引导读者进行批判性阅读,理解这篇文章背后复杂的政治光谱和舆论生态。

新闻原文

When great changes are afoot, we look for a user manual. There will be new patterns of living and new expectations for the future. The rapidly developing corruption landscape in the United States will be no exception. U.S. President Donald Trump's election last November and the accelerated institutional and personnel changes since his inauguration have forced Americans into new political territory. In particular, anti-corruption institu- tions and norms are unraveling. Attorney General Pam Bondi has ordered the Justice Department to prioritize cases related to criminal cartels and closed down Task Force KleptoCapture and the Kleptocracy Asset Recovery Initiative; Trump himself ordered a pause in new investi- gations or enforcement of the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act for six months. While those developments focus on U.S. businesses engag- ing in corruption overseas rather than at home, other anti- corruption norms are also coming under rapid and signifi- cant pressure. The Trump administration has fired at least 17 inspectors general-offices installed after the Watergate scandal as an independent check on mismanagement and abuse of power within government agencies-as well as sev- eral senior Justice Department employees. The president also issued an executive order that undermined the inde- pendence of agencies such as the Federal Trade Commission and Securities and Exchange Commission, both of which have important roles in detecting and punishing corruption. For some, these changes go beyond the usual shifts in pol- icy that come with a new administration. They seem to require a new vocabulary. For exam- ple, few people had heard of the word kakistoc- racy (a society governed by its least suitable or competent citizens) until it was the Economist's 2024 word of the year. Pundits have labeled the tech executives with the best seats at Trump's inauguration as America's new oligarchs; in his farewell address to the nation, President Joe Biden issued a warning that "an oligar- chy is taking shape in America." And in Feb- ruary, Sen. Bernie Sanders deployed a more dire descriptor still when he said the Trump administration was "moving this country very rapidly toward a kleptocracy."

What do these terms mean, both definitionally and in practice? And which, if any, can be accurately said to apply to the United States' oncoming political order?

THE FIRST DEFINITION REQUIRED is that of corruption itself. Cor- ruption is the building block of regimes considered antithet- ical to Americans and the American tradition yet has been frequently invoked across the political spectrum of late. "I campaigned on the fact that I said government is corrupt- and it is very corrupt," Trump said in an appearance with advisor Elon Musk at the White House in February. Indeed, rooting out graft in the so-called "deep state" bureaucracy is one of Musk's stated goals for the Department of Govern- ment Efficiency (DOGE), set up via executive order in Jan- uary. Among other accusations, Musk has said his team at DOGE discovered "known fraudsters" receiving payments from the federal government and that some people working in the bureaucracy, including at the U.S. Agency for Interna- tional Development (USAID), had been taking "kickbacks." Few would argue that fraud and waste are entirely absent from federal government spending. Last year, the U.S. Gov- ernment Accountability Office estimated that the federal government loses between $233 billion and $521 billion a year to fraud and that agencies had made about $2.7 trillion in improper payments over the last 20 years. The figures are huge, as with any organization spending more than $6 tril- lion annually. But do the documented instances of fraud in the U.S. government rise to the level of corruption?

While there is no universal definition of corruption, one of the most common, as defined by the advocacy group Transparency International, is "the abuse of entrusted power for private gain." For Musk to use this term in its proper sense in regards to USAID, for instance, he would have to demon- strate how USAID employees or contractors used the authorities granted to them in order to gain private benefits, such as by taking bribes or gifts in return for granting lucrative contracts. Receiving a duly authorized gov- ernment paycheck for implementing policies within one's job description does not count as "abuse of entrusted power" or "private gain" and thus would not qualify as corruption.

There are a variety of flavors of corruption. Currently, the most concerning kind is grand corruption. Grand corruption is when public institutions are co-opted by networks of ruling elites to steal public resources for their own private gain. It involves a wide variety of activities including bribery, extortion, nepotism, favoritism, crony- ism, judicial fraud, accounting fraud, electoral fraud, pub- lic service fraud, embezzlement, influence peddling, and conflicts of interest. In dismantling systems that protect against it, there are fears that the Trump administration could be opening the door to grand corruption in the future. Rep. Mark Pocan has criticized Musk's situation as a special government employee with federal contracts-at least 52 are ongoing, with seven government agencies-as "ripe for corruption" and plans to introduce a bill aimed at banning special government employees like Musk, who gave at least $277 million to sup- port Trump and other Republicans in last year's election, from obtaining such contracts. In a New York Times op-ed in February, five former Treasury secretaries expressed con- cern about "political actors" from DOGE gaining access to the U.S. payment system. This access, they wrote, endangered the security of a system previously handled exclusively by nonpartisan civil servants in order to prevent individual or partisan enrichment. (Musk told podcast host Joe Rogan in February that DOGE employees "go through the same vet- ting process that those federal employees went through.")

In contrast to grand corruption is the petty kind, which citizens encounter when asked for bribes or other favors in places such as hospitals, schools, and police departments. While pop culture is rife with storylines of corrupt cops and civil servants, such as in The Sopranos, most Americans have not experienced having to slip a little something extra to get their driver's license renewed or a child registered in the local public school. But, as the old saying goes, a fish rots from the head down. When grand corruption increases, lower level officials may feel even more emboldened to demand bribes in ways new to many Americans.

Kleptocracy takes corruption-even grand corruption- to a whole new level. There is not one specific definition of kleptocracy beyond that of "rule by thieves." As with grand corruption, a kleptocracy involves tightly integrated net- works of elites in political, business, cultural, social, and criminal institutions engaging in bribery, extortion, and other destructive actions. But additional characteristics make kleptocracy stand out even above grand corruption. First, the grand corruption in a kleptocracy is systemic, deeply networked, and self-reinforcing. Setting up a com- plex and highly lucrative corruption scheme is one thing, but transforming institutions to keep multiple streams of grand corruption through multiple networks ongoing for years or decades is a whole different level of kleptocratic wherewithal. Second, the consequences of a kleptocracy will distort long-term political and socioeconomic outcomes. While grand corruption schemes may amass elites billions of dol- lars, if those occur in a large enough economy, they may not necessarily impact the average citizen much. In a kleptoc- racy, the distortions are so massive that average citizens cannot miss the impacts on their lives. Third, in non-kleptocracies, grand corruption scandals may shock the conscience and grab headlines because they are not the norm. Such grand corruption in a kleptocracy is not an aberration but instead the unifying purpose and core function of the state. The scandals come so fast, so widespread, and so large that many citizens feel power- less to respond.

Key elites-referred to popularly as oligarchs-are instru- mental in a kleptocracy. Oligarchy is derived from the ancient Greek words oligoi ("few") and arkhein ("to rule"). Aristo- tle described oligarchy as "when men of property have the government in their hands." Per Aristotle's definition, to count as an oligarchy, the wealthy must be able to influence the government so to protect their wealth and power at the expense of the larger population. While the term is most associated with the hugely wealthy insiders who are part of Russian President Vladimir Putin's inner circle, some scholars argue that those described as Russian "oligarchs" do not technically meet the definition because while these individuals clearly have plenty of money, most do not seem to have much actual influence over domes tic or foreign affairs. Scholar Ilya Zaslavskiy instead refers to them as "kremligarchs" to signify their huge wealth but lack of actual political influence.

Democratic kleptocracies offer a different model of polit- ical power again. In Hungary, the ruling Fidesz party under Prime Minister Viktor Orban has been able to consolidate control over the parliament, courts, bureaucracy, and the media. Former U.S. Ambassador to Hungary David Press- man has summed up Hungary's system as an "embrace of nihilistic corruption." Companies linked to Orban's fam- ily and others in his inner circle receive highly preferential lucrative opportunities for government procurement con- tracts, for example, while those on the outside find their abil- ity to operate limited. Meanwhile, even though Hungary is in the heart of Europe, the press there is highly curtailed, to the point that one of its last independent radio stations was forced off air in 2021.

All kleptocracies are unique, and an American kleptoc- racy, were it to eventuate, would function differently from those in places such as Hungary, Iran, Russia, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, or Venezuela. Nonetheless, klep- tocracies share common characteristics, and there are signs a uniquely American form is already emerging.

SEEKING TO CATEGORIZE HOW KLEPTOCRACY OPERATES in differ- ent countries, scholar Michael Johnston has identified four major syndromes of corruption. The United States falls into the bucket of what he calls Influence Markets-the world's democratic good-governance leaders. No country considered an Influence Market has ever become a full-fledged kleptocracy. In an Influence Market, petty corruption is rare, and cases of grand corruption can lead to jail time, new legislation, and electoral losses, though there is often significant controversy over what should be considered legitimate lobbying or campaign contributions versus outright corruption. These countries display strong democratic norms, protect personal freedoms, advocate for human rights, and have independent courts and other enforcement agencies. The state is administered through a relatively clean, professional, and apolitical civil service.

The United States is the preeminent Influence Market country in the international system. It boasts the world's reserve currency and one of its strongest economies and big- gest militaries. Anti-corruption institutions and norms-as understood at the time-were written into the Constitution by the Founding Fathers or instituted shortly thereafter, including its system of checks and balances, emoluments clauses, Bill of Rights, and the requirements for represen- tatives to live in the districts and states that they represent. In 1977, the United States even became the first country to make it illegal to bribe another country's politicians, via the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act, which Trump has ordered a pause on enforcing.

There is no historical model for what happens when a great power that is also an Influence Market becomes a kleptocracy. Should the United States fall into kleptocracy, a few winners will benefit greatly. To be sure, inequality is not new, and several studies have shown that social mobility in the United States has been declining for years. Even so, a tilt toward klep- tocracy and fewer checks and balances would exacerbate an alarming trend line. In 2023, there were 1,050 billionaires in the United States, with a combined wealth of almost $5 trillion. In the third quarter of 2024, the top 1 percent of Americans held $49.23 trillion in household wealth, while the bottom 50 percent held only $3.89 trillion. Under an American klep- tocracy, the number of billionaires would likely grow along with the already disproportionate wealth of the top 1 percent.

In a kleptocracy, preferential policy access and outright grand corruption for oligarchs mean that procurement prices rise, public services are further privatized, and nit- picky fees abound. Thus, more public roads turn into toll roads, and businesses from airlines to hotels to credit cards can pile on the fees and sur- charges. The Trump administration's attempt to shut down the Consumer Financial Protec- tion Bureau, and the cessation of its investi- gative work, is a possible harbinger.

As oligarchs can further avoid taxation, taxes fall more heavily on the poor and mid- dle classes. Tariffs typify this trend, since they are taxes paid primarily by the consumer, not the supplier. Price increases from tariffs on food will hit the poor especially hard; the low- est income quintile of U.S. households spent 33 percent of their after-tax income on food in 2023, com- pared with the richest quintile, which spent only 8 percent.

Social programs-especially for a nation's poorest cit- izens are increasingly curtailed, underfunded, or cut entirely in a kleptocracy. The recently passed House budget proposes to extend Trump's 2017 tax cuts, which primarily benefited the wealthy, aiming to cut $2 trillion in spending over 10 years, including $880 billion in cuts to be determined by the House committee that oversees Medicare and Med- icaid funding. Recent comments by Commerce Secretary Howard Lutnick, immensely wealthy himself, that Social Security, Medicaid, and Medicare are "wrong" is a further worrying sign. Trump would not be the first Republican president to muse about cutting these programs, but early moves-including the proposal to slash hundreds of Veterans Affairs contracts-suggest that this administration's cuts may be more deep and widespread than its predecessors'.

Politicized institutions, especially law enforcement, are necessary to keep the kleptocracy going. As former Peru- vian dictator Óscar Benavides put it, "For my friends, every- thing; for my enemies, the law." Venezuelan and Russian companies, for example, know that being on the wrong side of the government brings the tax police, devastating tax bills, and bankruptcy, making the weaponization of the IRS a threat to all. This was something that President Richard Nixon understood when he provided his IRS commissioner an "enemies list" of some 200 Democrats for auditing, with the intent that they would be investigated and some even put in jail. The IRS commissioner had the list locked away rather than conducting the audits. The recent departure of the acting IRS commissioner and the firing of 6,700 proba- tionary workers during tax season, as well as DOGE's efforts to gain access to IRS and other taxpayer information, are also warning signs of such politicization.

Looking forward, other executive orders and policies, if implemented, could further push the United States toward kleptocracy. Most crucial is Schedule F (now called Schedule Policy/Career), laid out in October 2020 by the first Trump administration. It was rescinded by Biden and then rees- tablished via an executive order on the first day of Trump's second term. This executive order allows civil servants to be categorized into an employment grouping with fewer job protections, undermining 150 years of civil service reform. Implementing it would return the United States to the spoils system prevalent in the 19th century.

The result of these various executive orders and direc- tives, questionable personnel choices, a hamstrung Justice Department, undermined independent agencies, and the defunding and defanging of the civil service is that those who want to morph U.S. federal institutions for their own personal benefit are in positions of power to do so. More- over, the rapid-fire initiation of all of these efforts makes it harder for states, courts, civil society, and journalists to respond effectively; this is former Trump advisor Steve Ban- non's famous edict to "flood the zone with shit" in action.

Journalists in a kleptocracy are further constricted because libel laws may be skewed to make it easier for those in power to mount strategic lawsuits against media, civil society, or even ordinary citizens who might report on malfeasance to silence them. Musk and the administration's response to reporting that identifies DOGE employees is an early exam- ple of this. The narrative can be controlled in other ways, too. While Amazon founder Jeff Bezos's ownership of the Washington Post or Musk's ownership of X gets the most attention, conservative ownership of local media stations throughout the United States, such as Sinclair's network of nearly 200, makes them an important means to shape the pro-Trump message. In a globalized world, high quality- and often highbrow-media will remain available to those with the money, time, and willingness to access it. As Sergei Guriev and Daniel Treisman note in their book Spin Dictators, the availability of this media serves to prove that the regime is not actually that authoritarian while also making scape- goats of globalist elites who read the international, often paywalled, press.

Since the 2010 Citizens United decision, which allowed unlimited dark money to flow to federal election campaigns, what constitutes "corruption" for legal purposes has been very sharply curtailed. The most disturbing recent decision, however, is Trump v. United States (2024), which has given the president a remarkable amount of immunity so long as his actions are in some way linked to official acts. It also limits what presidential actions can even be investigated. Combined with the ability to pardon those involved in fed- eral cases, Trump and any future president have a great deal of legal leeway to bend the U.S. government to their will. Trump's pardon of cryptocurrency cult hero Ross Ulbricht-who ran a darknet drug market and had been sentenced to life in prison without the possibility of parole- and the administration's possible pressure on Romania to allow the departure of Andrew and Tristan Tate-under criminal investigation there for human trafficking and money laundering, among other charges-are ominous signs. When asked, Trump said he knew nothing about Romania's decision to lift the travel ban. (The fact that Flor- ida's attorney general has opened an investigation into the recently repatriated brothers, who deny the charges, is more promising.) Trump's executive orders targeting two law firms, one of which represents former special counsel Jack Smith, further serve to weaken the rule of law.

Despite promises to free up business, kleptocracies must intervene substantially in the economy. After all, one cannot ensure that economic benefits go to favored groups if the mar- ket is allowed to do its thing. In a well-governed country, for example, a procurement contract goes to the firm with the best bid and that has a track record of being able to do the work. But in a kleptocracy, most procurement contracts go to those in the right network or who paid the right bribes, not to the most qualified. The best documented example of klep- tocratic state capture of an economy is in South Africa, where a judicial commission found that former President Jacob Zuma and other state officials worked with the Gupta family to ensure that their companies received lucrative contracts with the government and state-owned companies while employing members and friends of Zuma's family. The massively overpriced contracts sucked tens of billions of dollars out of the economy and left a large hole in the federal budget. Among the detritus of the corruption and rot left over since Zuma's resignation in 2018 has been the mangling of the country's electricity grid, which in turn has undermined broader economic growth.

THE UNITED STATES IS NOWHERE NEAR South Africa in this regard. And it has often fallen short of its ideals in the past without surrendering its status as a liberal democracy. Yet Americans can gauge whether they are descending into kleptocracy sim- ply by observing whether their net worth and social network increasingly determine their rights and access to services.

Because the United States was already the most unequal country in the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, life for the wealthy in a kleptocracy would largely carry on as it has before-or may even improve. They can squat behind their private security and their walled communities. Their children can attend high-quality pri- vate schools and can play tennis and soccer at private sports clubs. Medical insurance and health care are already avail- able mostly to those who can pay or who have an employer willing to do so. Some wealthy communities will be able to maintain high-quality policing, fire departments, and other social services. For those who cannot pay or who do not happen to live or work in or near these fortunate subur- ban ink spots, the crumbs available for public services will continue to diminish, as will public security.

An opposition united against oligarchs is a kleptocracy's greatest threat, so they must maintain a divide-and-conquer strategy. In the 2024 presidential election, Trump increased his share of Black and Latino voters and barely budged with white voters, leaving some experts to describe polariza- tion as decreasing. But many of Trump's early decisions seem designed to reinflame polarization. For example, his sweeping pardon of the 1,500-plus people charged with crimes related to the Jan. 6, 2021, attack on the U.S. Cap- itol hardly seems geared toward uniting the country. The ongoing purge of military leaders, with some dismissals apparently linked to diversity, equity, and inclusion efforts, is further divisive. Particularly notable was the firing of the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, Gen. Charles Q. Brown Jr., along with the chief of naval operations, vice chief of staff of the Air Force, and the top lawyers for the Army, Air Force, and Navy. Generals have been fired before, includ- ing by Presidents Harry Truman and Barack Obama, but in Brown's case, there was no clear reason or obvious poor performance to point to. In fact, Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth had previously questioned if Brown, who is Black, had received his position because of his skin color.

Whether such actions, taken en masse, add up to full- fledged kleptocracy remains to be seen. But what is certain is that kleptocracy is a deliberate strategy rather than a for- tuitous opportunity. There is no "accidental kleptocracy." As a result, dekleptification studies show that the best time to dekleptify a society is whenever that society's rules and institutions are in flux, which in the United States is now. Normally, a dekleptification window stays open for up to two years, but this American example is moving so fast that there may be only months rather than years to react.

Civil society action through the courts has been the most effective countermove so far. Organizations such as Democ- racy Forward, a consortium of good-governance civil soci- ety groups, have been filing lawsuits on behalf of veterans, teachers, and the rights of average citizens. Likewise, states- especially blue states-have been filing lawsuits, including one alleging that DOGE's authority granted by Trump is unconstitutional.

People around the world have fought against kleptocratic networks, often successfully. That means there is a trove of dekleptification lessons learned for concerned Ameri- cans to adapt as part of developing their own strategies and tactics. USAID's Dekleptification Guide is considered the best synthesis of how to dekleptify a country; it examined case studies of both successful and unsuccessful deklep- tification from around the world to find the most useful strategies. While the document is no longer online, the anti-corruption community is working to make it avail- able to the public again. It is hardly the only guide. Srdja Popovic helped found the group Otpor! in Serbia, which successfully and nonviolently helped bring down President Slobodan Milosevic's kleptocracy. Since then, Popovic has worked through the Center for Applied Nonviolent Actions and Strategies to publicize successful nonviolent strate- gies, too. These are only two of the many global sources available. After decades of Americans trying to tell other countries' citizens how to fix their governments, it may be time to turn the tables.

As for grand corruption, Americans have their own history fighting back, including during the Gilded Age. They can look for and then elect committed anti-corruption reform- ers like Theodore Roosevelt, reinvigorate the muckraking of Ida B. Wells and Ida Tarbell, and reengage in the tactics of sit-ins, protest marches, boycotts, and other acts of resis- tance. These, after all, have been the hallmark of civil rights movements throughout U.S. history.

JODI VITTORI is a professor of the practice and co-chair of global politics and security at Georgetown University's School of Foreign Service.