中国如何赢得未来?

中国的产业政策因其规模庞大和雄心勃勃而备受全球关注,甚至被比作“曼哈顿计划” 。文章指出,中国的政策工具远不止是提供补贴,还包括监管标准和需求侧刺激等多种形式,并且其政策重心也随时间不断演变 。然而,研究也指出了一个关键问题——“产业同构” (industrial isomorphism),即大量城市集中选择相似的“关键”产业,如高端制造和人工智能 。

中国如何赢得未来?

How might China win the future?

新闻原文

How might China win the future?

IF CHINA DOMINATES the 21st-century economy, its industrial policy will get a lot of the credit. The state's efforts to cultivate new industries, breed winners and foster technological advances inspire awe and anger from outside observers. Kyle Chan of Princeton University recently compared China's policies to the Manhattan Project, which invented the atomic bomb. On present trends, he argues, "the battle for supremacy" in artificial intelligence (AI) will be fought not between America and China but be- tween leading Chinese cities like Hangzhou and Shenzhen. American officials may scoff-but they do not doubt the power of China's policy to distort markets. In March America's trade representative released a report criticising the "guidance, resources and regulatory support" that China's government bestows on favoured industries, at the expense of foreign rivals. The report called the "Made in China 2025" plan, which increased the country's share of industries like drones and electric vehicles, "far reaching and harmful". Such grievances help explain why President Donald Trump hit China with punishing tariffs in April.

One problem facing both critics and students of China's industrial policies is that it has so many. Its efforts are not confined to national plans such as Made in China 2025 or discrete undertakings akin to the Manhattan Project. They also take the form of obscure memoranda, lacking pithy names, issued by local officials- policies like Anqing City's "Notice on Supporting Large Commercial Circulation Enterprises In Carrying Out Pilot Projects For The Construction Of Modern Rural Circulation Systems". China churns out more than 100,000 policy documents a year. Over a fifth feature some kind of industrial policy, according to a new paper by Hanming Fang of the University of Pennsylvania, along with Ming Li and Guangli Lu of the Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shenzen. Not even the most diligent researcher could wrap their head around them all. Fortunately, one of the emerging industries that China is keen to promote-AI-can now help economists understand how China goes about its task.

Mr Fang and his co-authors used Google's Gemini, a large language model, to scour millions of documents issued from 2000 to 2022. They were scraped from official websites or obtained from PKUlaw.com, a vast repository. When properly prompted, Gemini could identify documents that met the definition of industrial policy. It could also discern the industries targeted and the tools used. To make sure the model was not making things up, the authors took precautions. They told the model to think of itself as an expert in Chinese industrial policy, and carried out random spot checks themselves. They then asked another model (from OpenAI) to refine the findings. The result is a rich database covering two decades' worth of Chinese efforts to win the future.

Their work captures the underappreciated variety of China's tools. Subsidies are most popular, appearing in 41% of policies. But they are only one tool out of 20 and often absent. Cheap credit and land are less common than you might expect, featuring in less than 15% of documents. Protection from foreign competition appears in only 9%. Instead of offering handouts, protection or perks, about 40% of central-government policies regulate the targeted industry by, say, imposing quality or efficiency standards. A few policies-3%-try to suppress industries that might be too dirty, inefficient or otherwise undesirable. Equating industrial policy with subsidies and tariffs, then, will "paint an incomplete picture of China's industrial-policy landscape", the authors warn.

That landscape has also changed over time. Tax breaks and ex- protectionism have become less fashionable. Government funds, which are supposed to act like venture capitalists, have become more so. Efforts to cultivate supply chains and clusters have also become more widely used. The same is true of policies to increase demand, such as government purchases or consumer subsidies. They appear in about a fifth of policy documents, roughly double their share in 2000. Often, city governments embrace these new tools before provincial or central governments.

One of the biggest surprises is that manufacturing-making in China-is targeted by only 29% of the policies. More focus on services; 17% are still dedicated to agriculture. Within these broad sectors, targeting can be savvy. City governments are more likely to pick industries that loom large locally, relative to their prominence province-wide, suggesting officials are playing to their city's strengths. This is particularly true in richer cities, where local governments may be more sophisticated.

Some cold water

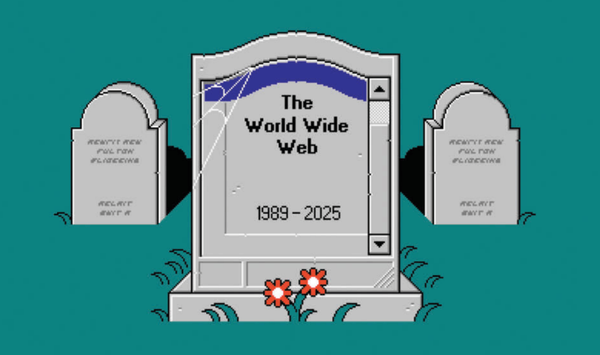

Targets are, however, becoming more similar. All 41 cities in the Yangzi River Delta have chosen "high-end manufacturing" as a "key" industry in their five-year plan, notes The Paper, a Chinese website. Thirty-eight have picked new-generation information technology, which includes AI. The delta, the paper worries, suffers from "industrial isomorphism".

Local governments may be converging on similar approaches because they are all trying to follow the central government's lead. Cities have become more likely to cite national policies in their own documents since 2013. They may also be emulating each other. Unfortunately, policies seem to become less effective as they spread from pioneers to laggards. Measures that lift firm revenues and profits in leading cities may fail to replicate in latecomers. Not everyone can have their own Manhattan Project.

Overall, the link between industrial policy and the productivity of firms is "mixed and tenuous" the authors say. But with the assistance of Gemini, they have shed some valuable new light on industrial policy's many variations. Maybe AI can help improve the design of policies to encourage emerging industries like AI.

文章分析

在动手编译之前,对原文进行一次“宏观把握”是至关重要的。这篇题为《中国如何赢得未来?》(How might China win the future?)的文章,深入探讨了中国庞大而复杂的产业政策体系,并介绍了利用人工智能(AI)这一前沿工具来分析这些政策的新研究方法。

文章体裁、文体与结构解析

这篇文章的体裁属于分析报道(News Analysis),它超越了简单的事实报道,旨在对“中国的产业政策”这一宏大议题进行深度解读。其文体延续了《经济学人》一贯的冷静、客观且逻辑严谨的风格,通过精确的数据和引述来支撑论点,例如,文章指出产业政策中“补贴是最受欢迎的,出现在41%的政策中”(Subsidies are most popular, appearing in 41% of policies),而“廉价信贷和土地的普遍程度则低于你的预期”(Cheap credit and land are less common than you might expect)。

在叙事结构上,该文巧妙地融合了倒金字塔结构与分析性框架。开篇便直接点出中国产业政策的巨大影响力,引用了“曼哈顿计划”(Manhattan Project) 的比喻和美国官方的批评,迅速抓住读者眼球。文章主体部分并未罗列枯燥的事实,而是围绕一篇利用AI分析海量政策文件的最新学术论文展开,从政策工具的多样性、历史变迁、地方政府的策略等多个维度进行了系统性分析。最后,文章在结尾给出了一个留有余味的结论:政策的整体效果“好坏参半且时而微弱”(mixed and tenuous),但AI为此类研究带来了新的希望。

信源、偏向与政治立场分辨

文章的来源《经济学人》(The Economist),是一家具有全球影响力的英国新闻周刊,其编辑立场通常被认为是古典自由主义和中间偏右,尤其在经济议题上,它一贯倡导自由市场经济。这种立场在文章中得到了微妙的体现。一方面,文章承认了中国产业政策的雄心与规模,但另一方面,它也通过引用美国贸易代表办公室的报告,称“中国制造2025”计划“影响深远且有害”(far reaching and harmful),来引入西方的批评视角。最终,文章借由学术论文的结论——产业政策与生产力之间的联系“好坏参半且时而微弱”(mixed and tenuous)——含蓄地表达了对政府主导产业政策有效性的审慎和怀疑,这与该刊的传统立场一脉相承。

跨文化与国际传播特征识别

作为一篇由西方主流媒体撰写的关于中国议题的报道,本文的跨文化传播特征十分明显。它试图向其全球读者(主要是西方受众)解释一个复杂的“他者”——中国的国家驱动型经济模式。文章将中国的海量政策文件描绘成一个“即使是最勤奋的研究人员也无法全部理解”(Not even the most diligent researcher could wrap their head around them all) 的复杂系统,而最终需要借助先进的AI技术(如Google的Gemini)才能“梳理”(scour) 和理解。这种叙事框架在一定程度上体现了以西方科技和学术方法为工具来解读和定义非西方现象的视角。

背景知识介绍

- “中国制造2025” (Made in China 2025):这是中国政府于2015年启动的一项旨在提升制造业核心竞争力的国家战略,重点聚焦于新一代信息技术、高端装备、新材料等十大领域,意图实现从“制造大国”向“制造强国”的转变。

- 产业政策 (Industrial Policy):指政府为影响本国产业结构、促进特定产业发展而采取的一系列干预措施的总和,其有效性在经济学界长期存在争论。

- 曼哈顿计划:“曼哈顿计划”(Manhattan Project)是第二次世界大战期间,美国为了抢在纳粹德国之前研发出原子弹而发起的一项规模空前的绝密科研与军事工程。 该计划从1942年持续到1946年,由美国主导,并得到了英国和加拿大的协助。普林斯顿大学的学者凯尔·陈(Kyle Chan)将中国的产业政策比作“曼哈顿计划”,因为两者具有以下类似的元素——宏大的国家战略目标、国家主导与资源总动员、聚焦关键领域与“培植优胜者”、紧迫感与竞争性。

建议文章的精炼和篇幅,本次将以全篇翻译的方式以完整保留其分析逻辑和微妙立场。

全译版本

如果中国主宰21世纪的经济,其产业政策将功不可没。这个国家为培育新兴产业、扶植优胜企业和推动技术进步所做的努力,让外界观察家们既敬畏又愤怒。普林斯顿大学的凯尔·陈(Kyle Chan)最近将中国的政策比作发明了原子弹的“曼哈顿计划”(Manhattan Project)。他认为,按照目前的趋势,人工智能(AI)领域的“霸权之争”将不会在美国和中国之间展开,而是在杭州和深圳等中国领先城市之间进行。美国官员或许会对此嗤之以鼻,但他们并不怀疑中国政策扭曲市场的力量。今年三月,美国贸易代表发布了一份报告,批评中国政府对其偏好的产业给予“指导、资源和监管支持”(guidance, resources and regulatory support),从而损害了外国竞争对手的利益。报告称,旨在提升中国在无人机和电动汽车等行业份额的“中国制造2025”(Made in China 2025)计划“影响深远且有害”(far reaching and harmful)。这些不满情绪,在一定程度上解释了为何特朗普总统在四月份对中国征收惩罚性关税。

无论是批评者还是研究者,在面对中国产业政策时都有一个难题:那就是政策实在太多了。中国的努力并不仅限于“中国制造2025”这类国家级规划,也不像“曼哈顿计划”那样是孤立的项目。它们还以地方官员发布的、缺乏简洁名称的模糊备忘录形式存在——例如安庆市的《关于支持大型商贸流通企业开展现代农村流通体系建设试点项目的通知》。中国每年出台的政策文件超过10万份。根据宾夕法尼亚大学的方汉明(Hanming Fang)以及香港中文大学(深圳)的李明(Ming Li)和卢光理(Guangli Lu)在一篇新论文中的研究,超过五分之一的文件涉及某种形式的产业政策。即使是最勤奋的研究人员,也无法将其全部掌握。幸运的是,中国正积极推动的新兴产业之一——人工智能——现在能够帮助经济学家们理解中国是如何开展这项任务的。

方教授和他的合著者们使用了谷歌的Gemini,一个大型语言模型,来梳理2000年至2022年间发布的数百万份文件。这些文件是从官方网站抓取,或是从一个庞大的资料库“北大法宝”(PKUlaw.com)获得的。经过适当的提示,Gemini能够识别出符合产业政策定义的文件,还能辨别出政策针对的行业和使用的工具。为确保模型不是在凭空捏造,作者们采取了预防措施。他们让模型将自己定位为一名中国产业政策专家,并亲自进行了随机抽查。随后,他们又让另一个模型(来自OpenAI)对研究结果进行完善。其成果便是一个内容丰富的数据库,涵盖了二十年来中国为赢得未来所做的努力。

他们的研究揭示了中国政策工具的多样性,这一点此前未得到充分认识。补贴是最受欢迎的工具,出现在41%的政策中。但这只是20种工具之一,并且也常常缺席。廉价信贷和土地的普遍程度低于你的预期,出现在不到15%的文件中。对外国竞争的保护仅出现在9%的政策里。中央政府约40%的政策并非提供直接补助、保护或优惠,而是通过施加质量或效率标准等方式来对目标行业进行监管。少数政策——3%——试图抑制那些可能过于污染、低效或存在其他问题的不良产业。因此,作者们警告说,将产业政策等同于补贴和关税,将会“描绘出一幅不完整的中国产业政策图景”(paint an incomplete picture of China's industrial-policy landscape)。

这幅图景也随着时间的推移而改变。税收减免和贸易保护主义已变得不那么时兴。本应扮演风险投资角色的政府引导基金则变得更为流行。旨在培育供应链和产业集群的举措也得到了更广泛的应用。旨在扩大需求的政策也是如此,如政府采购或消费者补贴。它们出现在大约五分之一的政策文件中,份额大约是2000年的两倍。通常,市级政府会比省级或中央政府更早地采纳这些新工具。

最大的意外之一是,制造业——即“中国制造”——仅是29%政策的目标。更多的焦点放在了服务业上;仍有17%的政策专门针对农业。在这些宽泛的领域内,政策的定位可能相当精明。市政府更倾向于选择那些在本地规模相对于全省更为突出的产业,这表明官员们正在发挥其城市的优势。在地方政府可能更为成熟的富裕城市,这一点尤其明显。

泼点冷水

然而,政策目标正变得越来越相似。据澎湃新闻(The Paper)这家中国网站指出,长江三角洲的所有41个城市都将“高端制造业”选为其五年规划中的“关键”产业。其中三十八个城市选择了包括AI在内的新一代信息技术。该报担心,长三角地区正遭受“产业同构”(industrial isomorphism)之苦。

地方政府之所以会趋向于相似的做法,可能是因为它们都在努力跟随中央政府的指引。自2013年以来,各城市在自己的文件中引用国家政策的可能性有所增加。它们也可能在相互模仿。不幸的是,当政策从先行者扩散到后进者时,其效果似乎会减弱。在领先城市能够提升公司收入和利润的措施,在后进城市可能无法复制成功。不是每个地方都能拥有自己的“曼哈顿计划”。

作者们表示,总体而言,产业政策与企业生产率之间的联系是“好坏参半且时而微弱的”(mixed and tenuous)。但在Gemini的协助下,他们为产业政策的多种形态提供了宝贵的新见解。或许,人工智能未来也能帮助改进那些旨在鼓励像人工智能这样的新兴产业的政策设计。【全文完】