濒临破产的英国大学正在寻求更低成本的模式

英国高等教育正陷入一场严重的财务危机 。其核心矛盾在于:一方面,政府长年冻结英格兰学生的学费,导致大学收入的实际价值不断缩水 ;另一方面,大学为吸引生源和提升全球排名,在豪华校园建设和行政人员扩张上支出巨大,存在严重的资源浪费 。这种模式将高昂成本转嫁给学生,使其背负世界最高的平均学费和沉重债务 。文章进一步剖析,当前大学间的竞争并非基于教学质量,而是依赖于校园设施和排名的“军备竞赛”,这是一种无效且加剧财务困境的结构性问题 。面对这一不可持续的局面,文章探讨了如“终身学习授权”和将大学分类管理等改革思路,并指出在期望不断升高而可用资金日益紧张的矛盾下,英国高教系统已到必须变革的关头 。

随着英国的学年步履蹒跚地走向尾声,大学看起来比一个刚结束了欧洲火车通票旅行的学生还要穷困潦倒。(译者注:Interrailing,即使用欧洲火车通票旅行,是欧洲年轻人中流行的一种长途、相对廉价的旅行方式,旅行结束后通常手头拮据。作者以此为喻,生动地描绘了大学的财务窘境。) 监管机构“学生办公室”(Office for Students)估计,四成的大学正处于亏损状态。行业组织“英国大学”(Universities UK, UUK)对60所院校进行的一项民意调查显示,半数大学已通过削减课程来节省开支。杜伦大学已裁员200人;纽卡斯尔大学的裁员数量也与此相近。工会方面则声称,兰卡斯特大学宣布的一项成本削减计划,可能会导致其近五分之一的学者失业。

政客们或许只会做些最基本的工作,以避免大型院校破产倒闭。这场危机的直接原因是英格兰学生的学费实际价值不断缩水:这项费用已被冻结多年。今年八月,政府将允许学费上涨——涨幅仅为几个百分点——这是八年来的首次。但工党政府尚未说明这是否只是一次性的小幅提升。大学校长们(译者注:Vice-chancellors,相当于英联邦国家大学系统中的“校长”或“校务长”。) 担心,新政府似乎无意将大学经费恢复到短短几年前的水平。

政府不投入更多资金是明智的。英国的大学曾享有世界上最高的预算之一;但并非所有这些资金都得到了明智的使用。然而,这个行业亟需关注。英国的高等教育过于同质化,倾向于浪费,并且痴迷于追求“世界一流”而非效率。重新设定混乱的激励机制,可以改善学生的处境,并帮助大学用更少的钱维持运营。

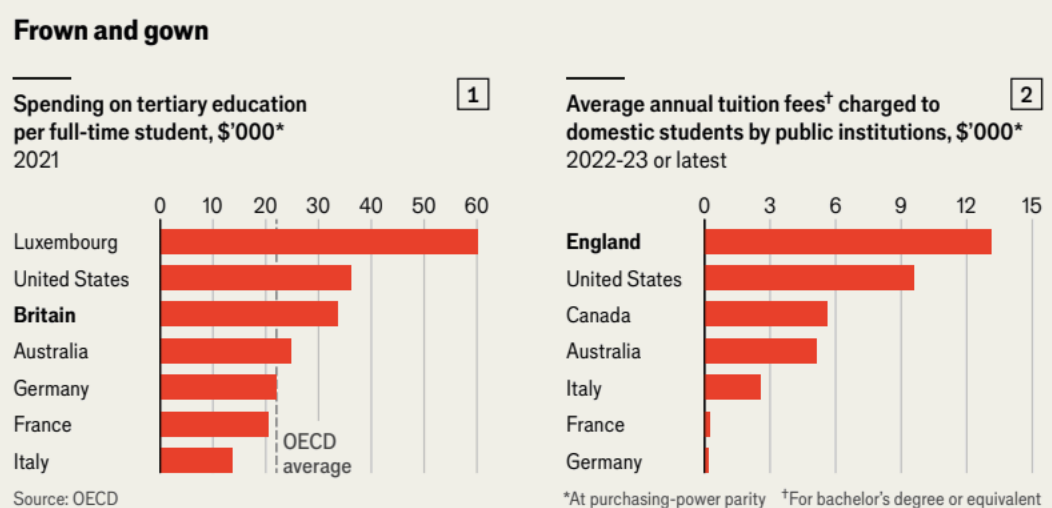

高等教育的怀疑论者坚称,这场财政紧缩终于在为那些长期以来贪得无厌的机构“合理瘦身”。(译者注:“right-sizing”,一个商业术语,表面意为“调整至合适规模”,但通常是“裁员”或“缩减规模”的委婉说法。) 2021年的数据显示,计算所有资金来源,只有卢森堡和美国的教育系统在每名注册学生身上投入的资金超过英国。当然,这里有很多需要说明的地方:按照国际标准,英国大学承担了大量的研究工作;其收入的一大部分都花在了这上面。然而,即使是行业内的大人物也承认,总的来说,英国的大学比国外的同行们拥有更多的现金。

此外,英国的系统在将多少成本转嫁给学生方面也非同寻常(见图2)。平均而言,英格兰的学费是世界上最高的。一旦将生活成本考虑在内,英格兰的本科生毕业时,平均每位借款人身负约45,000英镑(合60,000美元)的债务,而美国仅为约29,000美元。多年来,大多数英格兰毕业生都可以指望这部分债务得到豁免。然而,2022年对贷款制度的改革,已使得能够受益的人数大幅减少;今天的大多数借款人预计将在未来几十年里持续从工资中偿还贷款。

为何英国大学如此昂贵?

浪费性支出是部分原因。在2012年(当时学费翻了三倍)之后的几年里,大学们疯狂地投入到宏伟的校园建设计划中。在2014至2018年间,他们在基建项目上的花费,与英国举办2012年伦敦奥运会的开销相当。非学术人员约占大学员工总数的一半;一项研究发现,在2006至2018年间,“管理人员”和“专业人员”的数量激增了60%。其他国家的系统看起来更高效:澳大利亚的学生数量是英国的一半,但他们只用了四分之一数量的院校就容纳了这些学生。

大学方面并不同意。他们认为,高成本部分源于高期望。英国家庭已经开始期待一种在其他地方只有精英阶层才能享受的体验。英国大学的师生比约为1:14,而富裕国家的平均水平是1:18,澳大利亚约为1:20。大学校长们指出,英国拥有富裕世界中最低的学生辍学率,这或许部分归功于这种支持。

挥霍的冲动(译者注:此段小标题 “The urge to splurge” 意为“挥霍的冲动”。)

国外的年轻人通常选择住在家里,而英国的主流文化则是在家乡以外的地方上大学。在英国,只有不到20%的学生与父母同住,相比之下,爱尔兰约为40%,西班牙为50%。这增加了生活成本,也要求大学在宿舍、学生会和心理健康团队上投入大量资金。智库“高等教育政策研究所”的尼克·希尔曼(Nick Hillman)说:“每个人都期望我们的大学成为一个微型福利国家。”

在这两种关于“高浪费”和“高期望”的叙述之间,存在着第三类挑战,它使得缩减规模变得尤其棘手。英国高等教育的结构和资金特点本身就倾向于维持高成本。十年前,政府取消了招生人数上限。大学现在为了争夺生源而相互竞争,但方式并非政策制定者所希望的那样。事实证明,学生们对那些收取低于最高学费标准的大学唯恐避之不及,担心雇主会认为他们的学位是“打折货”。而大学也很难证明自己的教学质量优于别处,部分原因在于没有标准化的考试。于是,他们转而通过提供更宏伟的校园、更周到的学生关怀服务和更光鲜的营销来进行竞争。经济学家艾莉森·沃尔夫女爵(Dame Alison Wolf)说:“无论竞争取得了什么成就,它都没有降低成本。”

这场日益绝望的生源争夺战,也加剧了大学对全球排名的痴迷。“理解任何一所英国大学战略计划的最佳方式,就是他们想在排行榜上提升大约十个名次,”咨询顾问、前谢菲尔德哈勒姆大学校长克里斯·哈斯本兹爵士(Sir Chris Husbands)说。由于大学现在更加依赖支付高昂学费的外国学生,而这些学生的决定往往受排名驱动,这种执念正变得愈发严重。

然而,这类排名并不包含衡量学生学到多少东西的指标。它们使用的替代性指标,如师生比,奖励的是那些财大气粗的院校,而惩罚了那些进行创造性思考的机构。它们还奖励那些在研究上大肆投入的大学,尽管这并不一定能改善教学。因此,许多中等水平的大学感到有必要将资金投入到平庸的学术研究中,而这些钱本可以更好地用于教学。

那么,该如何驱动更好的价值呢?上届政府曾提议将学生贷款系统重新包装为“终身学习授权”(lifelong-learning entitlement),即给每个学生一个在线账户,内含其一生中可以借贷的最高额度。希望是这能激励学院和大学提供更短、更灵活的课程,并使学生对价格更敏感。

在更大胆的设想方面,智库EDSK的汤姆·里士满(Tom Richmond)和埃莉诺·里根(Eleanor Regan)在2021年的一篇论文中,构想将大学分为“国家级”和“地方级”机构。像牛津和剑桥这样的国家级大学,其任务将是攀登排行榜和吸引最聪明的头脑。而地方级院校则以尽可能最优的成本,提供尽可能最好的培训。

这种想法在英国仍然被视为激进,但在其他地方却司空见惯。现任政府版本的“终身学习授权”将于2027年启动。除此之外,其高等教育计划乏善可陈,远不及它对大学校长们的愿望清单那么长。政府要求他们为弱势学生创造更多机会;为当地社区做更多贡献;并为国家增长“做出更强有力的贡献”。对于那些正想方设法削减事务的大学来说,这一连串的指令简直是“不知人间疾苦”。(译者注:原文为 “tone deaf”,直译为“音盲”,引申为“不解风情、不识时务、不体谅他人处境”。) “你不能在削减可用资金的同时,不断提高期望值,”UUK的薇薇安·斯特恩(Vivienne Stern)说。或早或晚,总有些东西要撑不住的。【全文完】

原文分析

这篇文章深刻揭示了英国高等教育系统当前面临的严重财务危机,并探讨了其背后的深层原因和可能的出路。对于我们“川透社”的读者来说,理解这个话题需要一些背景知识。英国的大学,特别是英格兰地区的大学,其运营在很大程度上依赖于本国学生的学费。然而,正如文中所说,这项费用已连续多年被政府冻结,其实际购买力不断缩水,这是引爆危机的直接导火索。 1同时,大学为了在全球市场中竞争,尤其为了吸引支付高昂学费的国际学生,投入巨资进行校园建设和提升排名,导致开支居高不下。 这种“收入缩水”与“支出膨胀”的矛盾,构成了报道的核心冲突。

从体裁和文体来看,这篇报道属于典型的分析性新闻特写 (Analytical News Feature)。 它没有采用硬新闻常用的“倒金字塔”结构, 而是更接近《华尔街日报》体 (Wall Street Journal Structure), 但又融合了问题-原因-解决方案的分析框架。文章开篇以生动的比喻(“比刚结束欧洲火车旅行的学生还穷”)描绘危机,引人入胜;接着深入剖析危机产生的多重原因,包括资金来源问题、大学的浪费性支出、高昂的运营期望以及由排名驱动的无效竞争;最后探讨了可能的改革方向。 这种结构层次分明,逻辑严谨,引导读者进行深度思考。

文章来源是《经济学人》 (The Economist) ,这是一份享誉全球的英国刊物,其政治立场通常被认为是古典自由主义,经济上偏向自由市场和效率。 这种立场在文中体现得非常清晰:一方面,它批评了政府对学费的僵化管制;另一方面,它也毫不留情地指出大学自身存在“浪费”和“效率低下”的问题,并认为简单地注入更多政府资金并非良策。 这种批判性的、重在剖析结构性问题的立场,是我们在编译时需要准确把握和传达的。

从跨文化传播的角度看,这篇报道诞生于一个典型的“低语境文化” (Low-Context Culture) 环境中,其论述直白、依赖数据和逻辑分析。 在编译给相对“高语境”的中文读者时,我们需要注意将一些不言自明的背景(如英国的大学监管机构、副校长“vice-chancellor”的角色等)进行适当的解释,以弥合文化语境差异。

新闻原文

Leaner learning

Britain's bankrupt universities are hunting for cheaper models

AS THE ACADEMIC year in Britain limps to a close, universities look more broke than a student after a summer of Interrailing. The Office for Students, a regulator, reckons that four in ten universities are running deficits. Half have closed courses to save money, according to a poll of 60 institutions by Universities UK (UUK), an industry group. Durham has shed 200 staff; Newcastle a similar number. Unions allege that a cost-saving plan announced by Lancaster could see close to one in five of its academics lose their job.

Politicians will probably do the bare minimum to avoid big institutions going bust. The proximate cause of the crisis is the sinking real value of tuition fees for English students: these have been held frozen for years. This August the government will allow them to rise—by a few percent— for the first time in eight years. But the Labour government has yet to say whether this is merely a one-off bump. Vice-chancellors worry that it seems to have no desire to restore university funding to the levels of just a few years ago.

The government is wise not to pour in a lot more money. Britain's universities have enjoyed some of the highest budgets in the world; not all of that cash has been spent wisely. Yet the sector needs urgent attention. Higher education in Britain is too homogenous, inclined to wastefulness and obsessed with being "world class" rather than efficient. Resetting muddled incentives could improve things for students, and help universities get by with less.

Sceptics of higher education insist that the cash crunch is finally right-sizing institutions that have long gobbled up more than they need. Data from 2021 suggest that only Luxembourg and America have systems that bring in more money per student enrolled, counting all sources of funding (see chart 1 on next page). Caveats abound: Britain's universities undertake a lot of research, by international standards; a chunk of their income is spent on that. Yet even bigwigs in the sector admit that, by and large, Britain's universities have had more cash than peer systems abroad.

Moreover, Britain's system is unusual in how much of its costs get passed on to students (see chart 2). On average, tuition fees in England are the highest in the world. Once living costs are taken into account, bachelor's students in England graduate with debts of around £45,000 per borrower ($60,000), compared with only about $29,000 in America. For years the majority of English graduates could count on having a portion of this debt forgiven. Yet changes to the loan system in 2022 have shrunk how many will benefit; most of today's borrowers can expect to have their wages docked for decades.

Why are British universities so costly?

Wasteful spending is part of it. In the years after 2012 (when tuition fees were tripled) universities binged on grand campuses. Between 2014 and 2018 they shelled out as much on capital projects as Britain spent staging the 2012 London Olympics. Non-academics make up about half the university workforce; between 2006 and 2018 the number of "managers" and "professionals" swelled by 60%, finds one study. Other systems look more efficient: Australia has half as many students as Britain, but packs them into a quarter as many institutions.

Universities disagree. High costs, they argue, arise in part from high expectations. British families have come to expect an experience that elsewhere goes only to an elite. British universities have some 14 students for every teacher, compared with 18 on average in rich countries and around 20 in Australia. Vice-chancellors point out that Britain boasts the lowest student drop-out rates in the rich world, perhaps in part owing to this support.

The urge to splurge

Whereas youngsters abroad often stay at home, the dominant culture in Britain is to study outside one's own town. Fewer than 20% of students in Britain live with their parents, compared with around 40% in Ireland and 50% in Spain. That increases living costs. It also requires universities to spend a lot on dormitories, students' unions and mental-health teams. "Everybody expects our universities to be a mini welfare state," says Nick Hillman of the Higher Education Policy Institute, a think-tank.

Between these two narratives—of high waste, and high expectations—lies a third category of challenges that make downsizing particularly fraught. Features of the structure and funding of British higher education are inclined to keep costs high. A decade ago the government scrapped enrolment caps. Universities now fight each other for students, but not in the way policymakers hoped. Students have proved allergic to universities charging below the maximum fee, worrying that employers will think their degree was cut-rate. And universities have struggled to show that their teaching is better than elsewhere, in part because there are no standardised tests. Instead they compete by offering grander campuses, pastoral services and shinier marketing. "Whatever competition has achieved", says Dame Alison Wolf, an economist, "it hasn't reduced costs."

This increasingly desperate battle for students has also sharpened universities' obsession with global rankings. "The best way to understand any British university's strategic plan is that they want to rise about ten places in the league tables," says Sir Chris Husbands, a consultant and former vice-chancellor at Sheffield Hallam. With universities now more reliant on high-paying foreign students, whose decisions are often driven by rankings, that fixation is only getting worse.

Yet such rankings do not include measures of how much students learn. The proxies they use instead, such as staff-student ratios, reward big spenders and penalise institutions that think creatively. They also reward those that splurge on research, even though this does not necessarily improve learning. Hence many middling universities feel compelled to plough money into mediocre scholarship that might be better spent on teaching.

A diet of beans on toast?

How then to drive better value? The previous government proposed rebranding the student-loan system as a "lifelong-learning entitlement", in which every student was handed an online account with the maximum they could borrow over their lives. The hope was that this would incentivise colleges and universities to offer shorter, more flexible programmes and that it would make students more price-sensitive.

At the bolder end, a 2021 paper by Tom Richmond and Eleanor Regan, then at ESDK, a think-tank, imagined splitting universities into "national" and "local" institutions. National ones, such as Oxford and Cambridge, would be tasked with climbing league tables and attracting the brightest minds. Local outfits would offer the best possible training at the best possible cost.

Such thinking remains radical in Britain, but is quotidian elsewhere. The current government's version of the "lifelong-learning entitlement" will start in 2027. Beyond that, its plans for higher education are thin, unlike its wish list for vice-chancellors. It has asked them to create more opportunities for disadvantaged students; do more for their local communities; and "make a stronger contribution" to national growth. To institutions hunting for things to stop doing, the barrage of commands was tone deaf. "You can't continue to ratchet up expectations while ratcheting down the funding available," says Vivienne Stern of UUK. Sooner or later, something must give.