算法“围猎”青少年

曾是游泳健将的美国少女卡罗琳·科齐奥尔 (Caroline Koziol) 说,社交媒体平台Instagram和TikTok“毁了她的生活”。在疫情期间,一次为了保持体形的健康食谱和居家锻炼的无意搜索,让她陷入了算法推荐的“雪崩”之中,最终被诊断出严重的厌食症。如今,她是全美超过1800名原告之一,参与了一场针对科技巨头的史诗级诉讼。此案的核心并非指控平台上的有害“内容”,而是直指其产品“设计本身”——即那些为了最大限度攫取用户注意力而精心设计的算法和功能,是否具有成瘾性和危险性,从而对青少年造成了系统性的精神和身体伤害。

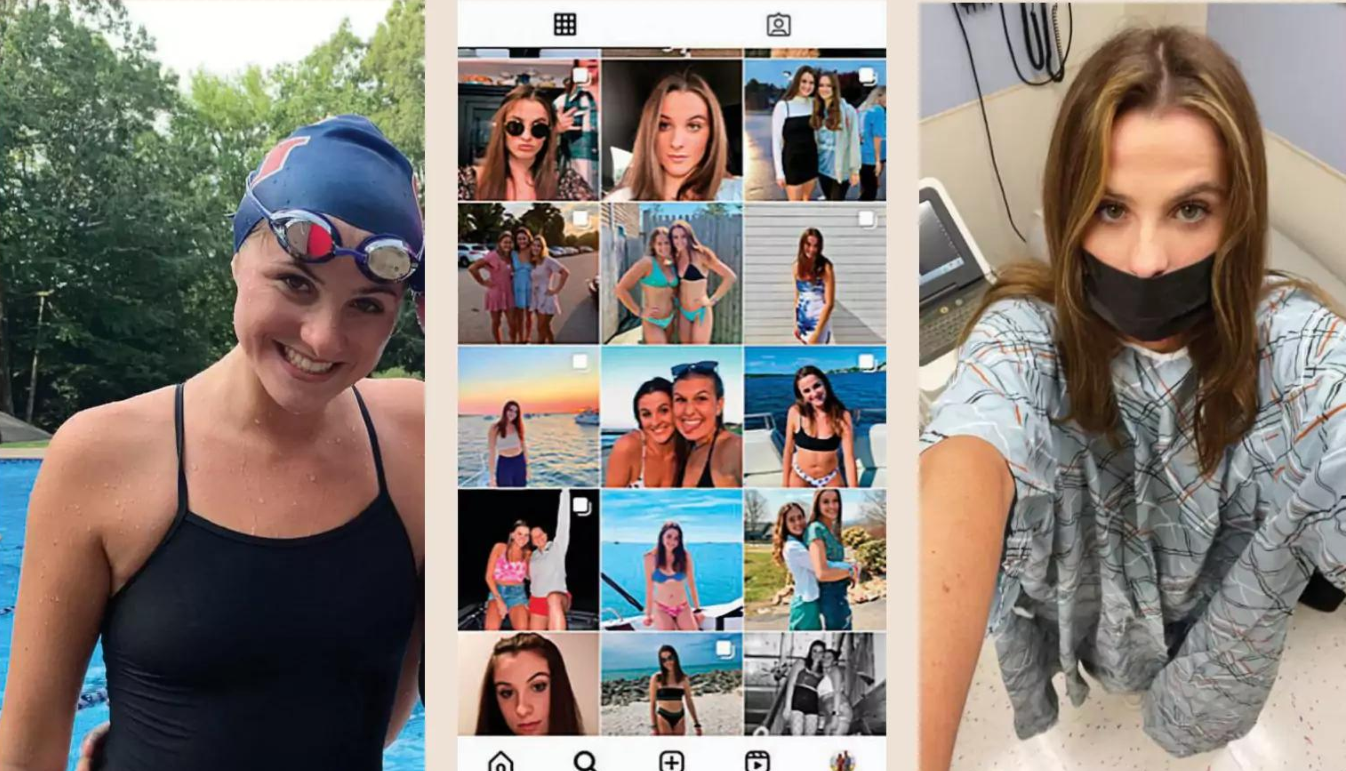

在高中一年级时,卡罗琳·科齐奥尔 (Caroline Koziol) 还是在康涅狄格州游泳锦标赛上角逐冠军的健将;但到了高三,她却连爬几步楼梯都会眼前发黑 。这期间,她陷入了饮食失调的深渊,而这一切始于新冠疫情期间她在社交媒体上的一次无意搜索。为了在泳池外保持体形,她开始在Instagram和TikTok上查找居家锻炼和健康食谱 。

几周之内,她的信息流就被各种宣传极端锻炼和饮食失调的内容所占据。“一次无辜的搜索,演变成了一场雪崩,”她回忆道,“它开始占据我的每一个念头。”

如今,21岁的科齐奥尔是全美超过1800名原告之一,他们共同参与了一场可能重塑科技公司社会角色的“多区合并诉讼” (multidistrict litigation, MDL)。原告方包括正在从心理健康问题中恢复的年轻人、自杀者的父母、不堪“手机成瘾”困扰的学区,甚至还有29个州的总检察长。他们共同指控社交媒体巨头的产品“具有成瘾性和危险性”,并且这些公司“不顾一切地追求增长,鲁莽地忽视其产品对儿童身心健康的影响” 。

这起诉讼的背景是美国青少年日益严峻的心理健康危机。2023年盖洛普的一项民意调查显示,美国青少年平均每天在社交媒体上花费近五个小时;而每天使用超过三小时的人,患抑郁和焦虑的风险会增加一倍 。美国前卫生部长维维克·默蒂 (Vivek Murthy) 甚至主张,应像对待烟草一样,在社交媒体平台上贴上警告标签 。

“他们正被这些公司、被这些扭曲的价值观和审美观念、被他们手中的电话所跟踪,”哈佛大学公共卫生学院的行为科学教授S.布林·奥斯汀博士 (Dr. S. Bryn Austin) 说,“无论他们在做什么,算法都能找到他们。”

原告方认为,这些公司清楚地知道其产品对年轻用户的潜在危害。根据《华尔街日报》2021年获取的内部文件,Facebook(现为Meta)早就知道Instagram正在损害少女的心理健康。一份内部研究的幻灯片写道:“我们让三分之一的少女对身材的看法变得更糟。”

此案最关键的策略,是绕开长期保护社交媒体平台的《通信规范法》第230条 (Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act)。该条款使平台无需为第三方发布的内容负责。然而,原告们并非起诉平台上的“内容”,而是基于“产品责任和过失”提起诉讼,指控平台有缺陷的“设计”——例如,旨在让用户(尤其是儿童)上瘾并持续使用的推荐算法 。正如科齐奥尔所说:“如果我只看到一两个视频,那没什么。但当我的信息流里全是这些内容时,事情就变得无法自控了。”

盖比·库萨托 (Gabby Cusato) 的故事则更令人心碎。她曾是一名长跑运动员,同样在15岁时陷入了算法的“兔子洞”。她的母亲凯伦 (Karen) 为她安排了密集的厌食症门诊治疗,但她一出治疗室,就又会回到手机上。2019年11月的一天,在一次争吵后,凯伦没收了女儿的手机。第二天早上,她发现15岁的盖比在自己的衣柜里自杀身亡。

“如果她早出生20年,这一切都不会发生,”凯伦说,“我做梦也想不到,一部手机会变成这样。”

面对诉讼,拥有Instagram的Meta公司表示,他们已推出了一系列新措施来保护未成年用户,例如默认为“青少年账户”模式,该模式会自动限制敏感内容、夜间关闭通知,并允许家长进行监督。

在厌食症治疗中心,科齐奥尔曾经历过一次“手机清理日”。当治疗小组的所有成员打开她们的手机时,她震惊地发现,尽管她们年龄、背景各不相同,但每个人的Instagram信息流看起来都和她的一模一样。“我们关注着同样的创作者,看着同样的帖子,完全相同的内容。”

“这让我明白,这个算法根本不在乎你是谁,”科齐奥尔说,“他们需要的,只是你的第一次搜索。” 如今,她虽然还在使用社交媒体,但必须时刻提醒自己:“只要我点开一次,明天就会看到另一条,然后是后天,日复一日,永无止境。”【全文完】

原文分析

这篇文章来自美国《时代》周刊,主题非常具有现实意义,探讨了社交媒体对青少年心理健康的深刻影响,并通过一个重大的集体诉讼案例,试图剖析科技巨头应该承担的责任。这篇报道充满了“人情味” (Human Interest) 和“影响力” (Impact)。

首先,这篇文章的核心背景是美国社会日益严峻的青少年心理健康危机,以及公众和法律界对社交媒体平台在其中所扮演角色的激烈争论。文章聚焦于一个大规模的“多区合并诉讼” (multidistrict litigation, MDL),有超过1800个原告,包括受害的青少年、他们的家庭、甚至学校和州政府,共同起诉Meta(Instagram的母公司)和TikTok等科技巨头。诉讼的关键点,也是这篇文章想要深入探讨的,并非平台上的“内容”,而是平台“产品本身的设计”——即它们的算法和功能是否故意设计得让人上瘾,从而对青少年造成了实质性伤害。这对读者来说是一个需要解释的背景知识,因为这挑战了长期以来保护科技公司的法律“避风港”——美国《通信规范法》第230条。

从体裁和文体来看,这无疑是一篇典型的特写新闻 (Feature Story) ,甚至可以说是深度报道 (In-depth Report) 。它没有采用硬新闻那种开门见山、罗列事实的方式,而是巧妙地运用了**“华尔街日报体” (Wall Street Journal Structure)** 的叙事结构。文章以游泳运动员卡罗琳·科齐奥尔 (Caroline Koziol) 因社交媒体陷入饮食失调的个人故事作为“钩子” ,迅速将读者带入情境,引发共情。随后,文章过渡到解释整个诉讼案背景和重要性的“核心段落” (Nut Graf) ,接着通过专家访谈、数据统计、法律分析以及第二个更具悲剧色彩的故事(盖比·库萨托之死)来层层深入,最后又回到卡罗琳的现状,形成首尾呼应的闭环结构 ,给读者留下深刻而持久的印象。

在信源和立场方面,原文发表于《时代》周刊,根据AllSides等机构的评估,这家媒体的立场**“偏左” (Lean Left)**。这一点在文章中体现得非常明显:叙事角度完全站在受害者一方,通过大量饱含情感的个人故事和措辞(如“毁了我的生活”、“被这些公司跟踪”)来塑造科技公司的负面形象 。虽然文章包含了Meta公司的回应,但其篇幅和说服力远不及原告方和批评者的声音,这是一种典型的**“信源选择偏向” (Bias by Selection of Sources)** 。

最后,从跨文化传播的角度看,这篇报道深深植根于个人主义(Individualism) 和低权力距离 (Low Power Distance) 的西方文化语境中。它通过聚焦个体悲剧来揭示宏大的社会问题,并体现了挑战和问责大公司(科技巨头)权威的“监督者”精神 ,这对于我们的读者来说,既有普世的共鸣点,也存在一定的文化差异,编译时需要特别注意。

编译分析

基于以上分析,我建议我们采用

节译 (Abridged Translation) 的方式来处理这篇文章。原文篇幅较长,包含了大量关于美国司法程序(如MDL、第230条款)的细节和多位律师、专家的引语,如果进行全译,对于不熟悉这些背景的“川透社”读者来说,可能会显得信息过载、枯燥难懂 。节译能让我们在保留原文核心冲击力和思想深度的同时,使文章更紧凑、更聚焦,也更符合我们网站读者的阅读习惯 。

具体的节译步骤可以这样规划:

第一,保留并突出核心故事线。卡罗琳和盖比的故事是文章的灵魂,我们必须完整保留她们如何接触社交媒体、算法如何将她们推向深渊、以及这对她们生活造成的毁灭性影响的关键情节。这是抓住读者的根本,也是文章“人情味”的集中体现。

第二,提炼和概括背景信息。对于复杂的法律概念和大量的统计数据,我们不必逐一翻译。可以将其整合、简化,用概括性的语言清晰地告诉读者:这场官司在告什么(产品设计缺陷)、由谁在告(广泛的社会联盟)、以及它为什么重要(可能改变科技行业的规则)。挑选一两个最有代表性的数据(如美国青少年日均使用社交媒体时长)来支撑观点即可。

第三,精选关键引语。原文中有多处专家和律师的引语,我们不需要全部保留。可以选择一两句最震撼、最能概括核心论点的引语,比如哈佛大学奥斯丁博士所说的“他们被手中的电话所跟踪”,或者律师卡罗尔所说的“我认为他们在一代年轻人身上做了实验”。同时,为了保持平衡,也应简要转述Meta公司的主要辩护观点(如已推出“青少年账户”等保护措施)。

第四,遵循“以小见大,首尾呼应”的结构。我们的节译版本应该努力再现原文精巧的叙事结构。同样以卡罗琳的故事开头,然后引出诉讼大背景,再用盖比的故事将情感推向高潮,最后以卡罗琳的现状结尾。这样能确保节译稿件依然具有强大的叙事张力和情感感染力。

通过这样的处理,我们既能忠实地传达原文的核心信息与立场,又能使译文更符合“川透社”的风格和读者需求,实现跨文化传播效果的最大化。

新闻原文

Caroline Koziol says Instagram and TikTok ruined her life. Now she's one of hundreds of plaintiffs fighting back

By Charlotte Alter

AS A FRESHMAN IN HIGH SCHOOL, CAROLINE KOZIOL competed in the Connecticut statewide champion- ship, swimming the 100-yd. butterfly in just over a minute. By senior year, she could barely climb the stairs without seeing black spots. In September 2021, Koziol's coach had to pull her out of the pool after she nearly passed out during swim practice. "My coach was like, Just eat a granola bar. You'll feel better," says Koziol, now a college junior. "And I was like, 'That's absolutely not going to happen."

Back then, Koziol was deep in the grips of an eating disorder that shattered her adolescence. Now, she's suing the social media giants Meta and TikTok, alleg- ing that the design of their products contributed to her anorexia and made it more difficult for her to recover. When Koziol was stuck at home during the COVID- 19 pandemic, she started looking up at-home work- outs on social media to keep herself in shape for swim- ming, and searched for healthy recipes to make with her mom. Within weeks, her Instagram and TikTok feeds were full of content promoting extreme work- outs and disordered eating. "One innocent search turned into this avalanche," she says, sipping iced coffee at a shop near her parents' home in Hartford. "It just began to overtake every thought that I had."

KOZIOL, NOW 21, is among more than 1,800 plain- tiffs suing the companies behind several leading social media platforms as part of a case that could reshape their role in American society. The plaintiffs include young adults recovering from mental-health problems, the parents of suicide victims, school districts dealing with phone addiction, local governments, and 29 state attorneys general. They've joined together as part of a multidistrict litigation (MDL), a type of law- suit which consolidates similar complaints around the country into one case to streamline pretrial proceed- ings, which is now moving through federal court in the Northern District of California.

The plaintiffs allege that the products created by social media giants are "addictive and dangerous," that the defendants have "relentlessly pursued a strategy of growth at all costs, recklessly ignoring the impact of their products on children's mental and physical health," and that young people like Caroline Koziol are the "direct victims of intentional product design choices made by each defendant."

The MDL is expected to reach trial next spring. It comes as social media is monopolizing more and more attention from children and teens. The average teen- ager in the U.S. spends nearly five hours per day on social media, according to a 2023 Gallup poll; those who spend more than three hours on it daily have double the risk of depression and anxiety. One study found that clinical depression among young people was up 60% from 2017 to 2021, which critics attribute partly to rising social media use. Overall, 41% of teens with high social media use rate their mental health as poor or very poor, according to the American Psychologi- cal Association. "Social media is associated with sig- nificant mental health harms for adolescents," wrote former surgeon general Vivek Murthy, who argues for putting warning labels on social media platforms as the U.S. does with tobacco.

As some of the most powerful companies in the world work to monetize their attention, kids across the country are struggling with the consequences of social media addiction. "They're being stalked by these companies, stalked by these really disturbed values and beauty ideas, stalked by the phone in their hand," says Dr. S. Bryn Austin, a professor of behavioral science at the Harvard School of Public Health. "The algorithm is finding them no matter what they're doing." To crit- ics, there's little question why: Austin co-published research which estimated that in 2022 alone, children under 17 delivered nearly $11 billion in advertising rev- enue to Facebook, Instagram, Snap, TikTok, Twitter, and YouTube.

Legislative efforts to regulate social media companies have mostly stalled in Congress, and the plain- tiffs' attorneys in the social media MDL say this case represents the best hope of holding these tech com- panies accountable in court-and getting justice for those who have been harmed. The MDL, says co-lead plaintiffs' lawyer Previn Warren of Motley Rice, is a "giant coordinated siege by families and AGs unlike anything we've seen since the opioid crisis."

The plaintiffs argue the companies were aware of the ramifications for young users, yet designed their products to maximize addictiveness anyway. Internal documents obtained by the Wall Street Journal in 2021 suggest that Facebook, now Meta, knew that Insta- gram was harming girls' mental health: "We make body image issues worse for 1 in 3 teen girls," said one slide presenting internal research. (Meta disputes this characterization, saying the same internal research shows teen girls were more likely to say Instagram made them feel better than worse.)

"These companies knew that there was a disproportionate effect on young women," says Koziol's law- yer, Jessica Carroll of Motley Rice. She represents eat- ing disorder clients as young as 13 years old, including some who have been on social media since they were 10. "I think that they experimented on a generation of young people, and we are seeing the effect of that today"

Suing social media companies is a difficult challenge. Most digital speech is protected by the First Amendment, and social media platforms have long asserted protections under Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act, which grants them immunity from liability for content they host. But the plain- tiffs in the MDL aren't suing over content. They're suing on product liability and negligence grounds, alleging that defective design features hook children to the platforms and allow them to evade parental consent, while the recommendation algorithms ma- nipulate kids to keep them on the apps. Koziol isn't suing Instagram's and TikTok's parent companies for hosting content that drove her to an eating dis- order. She's alleging that the platforms are designed to maximize her engagement, and as a result, she was drawn deeper and deeper into anorexia content. "If I saw one or two videos, it wouldn't have made a dif- ference," Koziol says. "But when it was all that I was seeing, that's when it became obsessive."

Critics say that bombardment is a deliberate feature, not a bug. "They have a machine-learning recommendation system that is oriented towards growth at all costs," says Carroll, "Which means anything to keep eyeballs on it."

Meta, which owns Instagram, says it has sought to combat the harms experienced by underage users by rolling out new restrictions. As of last year, any Insta- gram user from the ages of 13 to 18 will default to what Meta calls a teen account, which is automatically private, limits sensitive content, turns off notifications at night, and doesn't allow messaging with anyone with- out mutual contacts. The teen accounts are meant to address key concerns that parents have about teens on the app, which Meta spokeswoman Liza Crenshaw described as "content, contact, and time." Meta has also developed "classifiers," she said-AI programs that scan for problematic content to remove.

"We know parents are worried about having un- safe or inappropriate experiences online, and that's why we've significantly changed the Instagram experience for tens of millions of teens with new teen accounts," Crenshaw said in a statement to TIME. "These accounts provide teens with built-in protec- tions to automatically limit who's contacting them and the content they're seeing, and teens under 16 need a parent's permission to change those settings. We also give parents oversight over the teens' use of Instagram, with ways to see who their teens are chatting with and block them from using the app for more than 15 min- utes a day, or for certain periods of time, like during school or at night."

Despite repeated requests, TikTok did not provide a comment for this story.

CAROLINE KOZIOL'S PARENTS thought she was too young for social media as a preteen. But many of her friends in elementary school already had accounts on Instagram and TikTok, and Koziol felt left out. Both platforms have an age limit of 13. Koziol says she signed up when she was 10 or 11. "I was able to lie about my age really easily and make an account," she recalls. "My parents had no idea."

Age verification is an "industry-wide challenge," says Crenshaw, adding that this year Meta started testing a new AI tool designed to proactively find ac- counts of teens masquerading as adults and transition them to teen accounts. Meta supports federal legislation that requires app stores to get parental approval whenever a teen under 16 downloads an app.

As a competitive swimmer, Koziol had spent much of her life in a bathing suit, and was comfortable in her body. "I never thought twice about other people's bodies or my own," she says. What she cared about was her athletic career. Her dream was to swim competitively in college. Then she began spending time on Insta- gram and TikTok. "I started using social media, and I'm like, 'Oh, I have really broad shoulders compared to a lot of girls," she recalls. "Or, 'Oh, my thighs touch,' whereas the fitness influ- encers, their thighs don't."

When the pandemic hit, her school went remote and swim practice was canceled. Koziol knew that even a few days away from the pool could weaken her endurance and make her less competitive. Worried about losing muscle mass, she searched on Instagram for "30 minute at-home work- out," or "cardio workout at home." She was also filling free time by baking with her mom, and started looking up healthy recipes to make. "My searches were never 'low calorie, low fat," Koziol says. "It was 'healthy."

The dramatic evolution of the content the algorithm served to her was apparent only in retrospect. "It was so nefarious," she says. Searching for healthy recipes led her to low-calorie recipes. Searching for at- home workouts led her to videos of skinny influencers in workout clothes, "body checking" for the camera. "Something in my algorithm just switched," she says. "There was nothing I could do." A healthy teenager who wanted to see memes and funny videos and ex- change messages with her friends suddenly had her feed filled with "very thin girls in workout clothing, showing off their bodies."

Before too long, her daily diet shrank to just a protein bar or two. Sometimes she ate nothing at all until dinner. For months she subsisted mostly on baby puffs and Diet Coke-"Just to fill my stomach"-even as she forced herself to do hours of cardio. Meanwhile, the al- gorithms supplied images of skinnier and skinnier girls, on more and more extreme diets. Other users chimed in with comments on those posts, Koziol says, suggesting tips and tricks to "feel like you're eating something." She kept her car stocked with paper towels, wipes, and extra mascara so that she could reapply makeup after forcing herself to vomit on the side of the road.

By her junior year, "I was addicted to this empty feeling," Koziol says. Being on social media was like "getting sucked into a dark hole." She lost 30 lb. in a year. Her eating disorders led to issues with her throat and teeth, and hormonal problems that caused hot flashes and night sweats; her brain felt fuzzy as her short-term memory faltered from malnutrition. "I was like a zombie," she says. "I was not the same person."

Her parents realized something was wrong, and Koziol started outpatient treatment for anorexia the summer after junior year. She met with psychiatrists, dieticians, and therapists. Nothing could break the algorithm's grip. "When my thoughts correlated with what I was seeing on my phone, it just felt normal," she says. "I really didn't even see a problem with it."

Senior year she missed half her classes to attend treatment. She wasn't able to take the AP course load she'd hoped, and only graduated because of all the extra credits she'd taken earlier in high school. In- stead of going to college, she went to Monte Nido, an inpatient anorexia-treatment facility in Irvington, N.Y.

Dr. Molly Perlman, the facility's chief medical officer, says that while many eating disorders have an underlying genetic component, they're triggered by social environments-and photo-based social media platforms are a perfect trigger. Perlman says that not only have those apps contributed to the rise of eating disorders, they've also made them far more difficult to treat. "The algorithms are very smart, and they know their users, and they know what they will click on," Perlman says. "These are malnourished, vulnerable brains that are working towards finding recovery, and yet the algorithms are capitalizing on their disease."

Toward the end of Koziol's six-week stay at Monte Nido in the summer of 2022, her therapy group had a "phone cleansing day." All the patients were asked to either delete social media altogether or to block harmful hashtags. The facility was filled with women of different ages, races, backgrounds, and hometowns. But when everyone opened their phones, Koziol noticed that their Instagram feeds looked just like hers. "We had the same creators," she says. "The same posts, the exact same content." For all their differences, these women were being fed the exact same pro-anorexia content. "It showed me that this algorithm doesn't care about who you are," Koziol says. "All they need is that first little search."

GABBY CUSATO'S STORY started out a lot like Koziol's. Gabby was a competitive athlete too, a cross-country runner. She was part of a tight-knit family from up- state New York-a quadruplet, with two older siblings and loving parents.

Gabby's parents got her a phone in seventh grade to help the family coordinate pickups from multiple different sports practices. She had one Instagram account her parents knew about and several others that were secret. "Imagine being 15. You want to be fast, you want to be skinny," says Gabby's mother Karen. "And if some- body's saying to you, here's how you can do it, here's how you can lose more weight-it's just a rabbit hole."

After her drastic weight change, Karen Cusatoen- rolled Gabby in intensive outpatient treatment for anorexia. She went three days a week for four hours a day. But as soon as she got out of therapy, she would be back on her phone. One of her Instagram accounts was de- voted to her eating-disorder treatment; Gabby posted pictures of healthy meals she ate during her recovery. Jessica Carroll, who also represents the Cusato family, says this account may have aggravated Gabby's problem. "By creating this account," Carroll says, "she's almost inviting the algorithm to send her more of this stuff."

One day in November 2019, Karen Cusato confiscated Gabby's phone after an argument and sent her to her room, thinking that her daughter could cool off and they could patch things up in the morning. The next morning, Gabby's bed was made, but she was no- where to be found. At first, Cusato and her husband thought she had run away. "Then we found her in the closet," Cusato recalls. "The scream from my husband is something that I can never unhear." Gabby had died by suicide. She was 15.

Most days, Cusato blames herself. But she knows this would not have happened if Gabby had not become so addicted to social media. "If she was born 20 years earlier, this would not have taken place," she says. If Cusato could do it again, she'd buy her daughter a phone without internet access. "Never in my wildest dreams did I think this was what the phone could turn into."

"I think she felt less than perfect," Cusato says. "The algorithms were giving an ideal weight for an ideal height, and she was chasing that number, and, you know, she didn't get to that number that she thought was going to make her happy." Anorexia has the highest mortality rate of any psychiatric disorder, not just because of the malnutrition involved, but be- cause it's often clustered with depression, anxiety, and suicidal ideation. Carroll says that nearly half of the personal-injury cases represented by her firm in the MDL are related to eating disorders.

Cusato has been a high school math teacher for more than two decades. Every day she stands in front of classes of kids who are the same age Gabby was when she died. During the years she's spent in the classroom, she's noticed a change take place in her students. "Were kids depressed before? Yes," she says. "Were they de- pressed in the numbers they are now? Absolutely not."

THE SUITS FILED by Koziol, the Cusatos, and others represent a new phase in the effort to combat so- cial media harms. "The strategy of these companies is to do anything they can to distort the language of Section 230 to protect them with impunity," says Mary Graw, a law professor at the Catholic Univer- sity of America who has written extensively about Section 230. "As a result we have an unregulated in- dustry which is used by most of the globe with the potential to cause massive harm, and no way to look under the hood to see what the industry is doing. It is stunning. No other industry has such avoidance of accountability."

The social media MDL cleared a major obstacle in November 2023 when a federal judge in California ruled that many of the lawsuits could proceed. While Judge Yvonne Gonzalez Rogers narrowed the scope of the litigation, she ruled that many of the negligence and product liability claims are not barred by either the First Amendment or Section 230.

Multidistrict litigation is often slow and unwieldy, since it contains many distinct cases with different plaintiffs seeking different damages. The school districts, for example, want something different than the attorneys general do. Personal-injury plaintiffs like Koziol and the Cusatos are seeking compensation for medical bills, pain and suffering, and punitive damages for what they say was "reckless, malicious conduct" by the social media companies. They also want injunctive relief a formal ruling from the judge stating that the platforms are defectively designed, and court orders requiring the companies to remove addictive or danger- ous features, add warnings, and strengthen safeguards.

The fact-discovery phase of the case, in which both par- ties exchange documents and testimony, closed in April. The two sides are pre- paring for a motion of summary judgment in the fall, when the judge will decide if the case will go to trial.

Koziol can't point to any one piece of content that caused her eating disorder. To her, "it's the constant bombardment of all of these videos" that led her to the brink of starvation. "No third party is responsible for the algorithm," she says. "That's Meta and TikTok alone."

While she's seeking financial compensation for her eating-disorder treatment as well as other financial damages, Koziol says the purpose of the suit is to hold those corporations accountable. "They knew what they did was wrong," she says. "What they were doing was harming young girls. And it ruined my life."

Koziol had been accepted to her dream school, the University of South Carolina. She had imagined joining a sorority and going to SEC football games on Saturdays. She even had a roommate lined up before she decided to take a year off to focus on her recovery. By the time she was ready for college, her therapists warned her that going so far away could trigger a re- lapse. Instead she enrolled at University of Hartford, closer to home. Greek life and football aren't in the cards right now. She's not on the same track as most of her old friends. She had to quit swimming.

Even after everything she's been through, Koziol can't bring herself to delete her social media entirely; Instagram is so ubiquitous that it feels impossible to be a young person without it. She's blocked certain hashtags from her Instagram, reset her account, and unfollowed harmful creators. Still, the algorithm finds ways to tempt her. "It's taken a lot of work to not interact with the dis- ordered content that occasionally comes up," she says. "I always have to remind myself: the second I click on it, I'm gonna get another post tomorrow, and then an- other post tomorrow, and then another post tomorrow."